Sometime in the fall of 2016, I received an odd message on Facebook. An ethnic Circassian whom I’d never met thanked me for helping him learn Turkish. This was a very strange message, as I don’t even speak Turkish. How could I have helped him learn it?

As it turned out, my fellow Circassian – let’s call him Wa’el – was originally from Syria. He had fled to Turkey as the war waged on there. And he was one of the millions of other Syrians, tens of thousands of whom were ethnic Circassians. Back in Syria, Wa’el was part of a Circassian language study group. And he had used my materials to teach himself Circassian.

The Circassian Language’s Trek Toward Extinction

In case you’re confused, here’s a brief sidebar. There are an estimated 5 million ethnic Circassians in the world. In proportional terms, Circassians make up the largest diaspora in the world. An estimated 90 percent live outside their historical homeland in the North Caucasus of the Russian Federation.

At the time of their expulsion, they spoke Circassian but there was no written form of the language. So, although people (like my mother and father) may be fluent in the language, they are illiterate. Due to a variety of circumstances, the vast majority of ethnic Circassians don’t speak their ethnic language. The situation is somewhat parallel to the decline of Gaelic among ethnic Irish. Even in Ireland, Gaelic is on the decline, and a similar trend is at work with the Circassian language.

The Circassian language is currently considered “at-risk” by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). By some estimates, fewer than 20% of the world’s ethnic Circassians speak the language. And that number will likely decrease to 10% over the coming decades.

How Grassroots Language Learning Evolved into Something New

Having succeeded in teaching myself how to speak, read, and write Circassian, I received tons of requests to share my study notes and learning materials. What began as a collection of handwritten notes morphed into a series of PowerPoint presentations and video lectures. Eventually, I established a teaching program at the Circassian Benevolent Association in Wayne, New Jersey. Over the course of several years, I taught the language to several hundred people aged five to 65.

It was an amazing experience for me. I wrote and rewrote my materials, sat in front of large groups of students, and ran in-class exercises and drills. I also had the opportunity to interact with children, young adults, working professionals, and senior citizens. In the end, I learned a lot about how people engage in the language learning process.

This was a bit of a golden era for me. Teaching others improved my own language abilities. And seeing how people struggled with or embraced my methods helped me refine my methods and materials. During this time, it’s safe to say that I worked directly with at least 500 people.

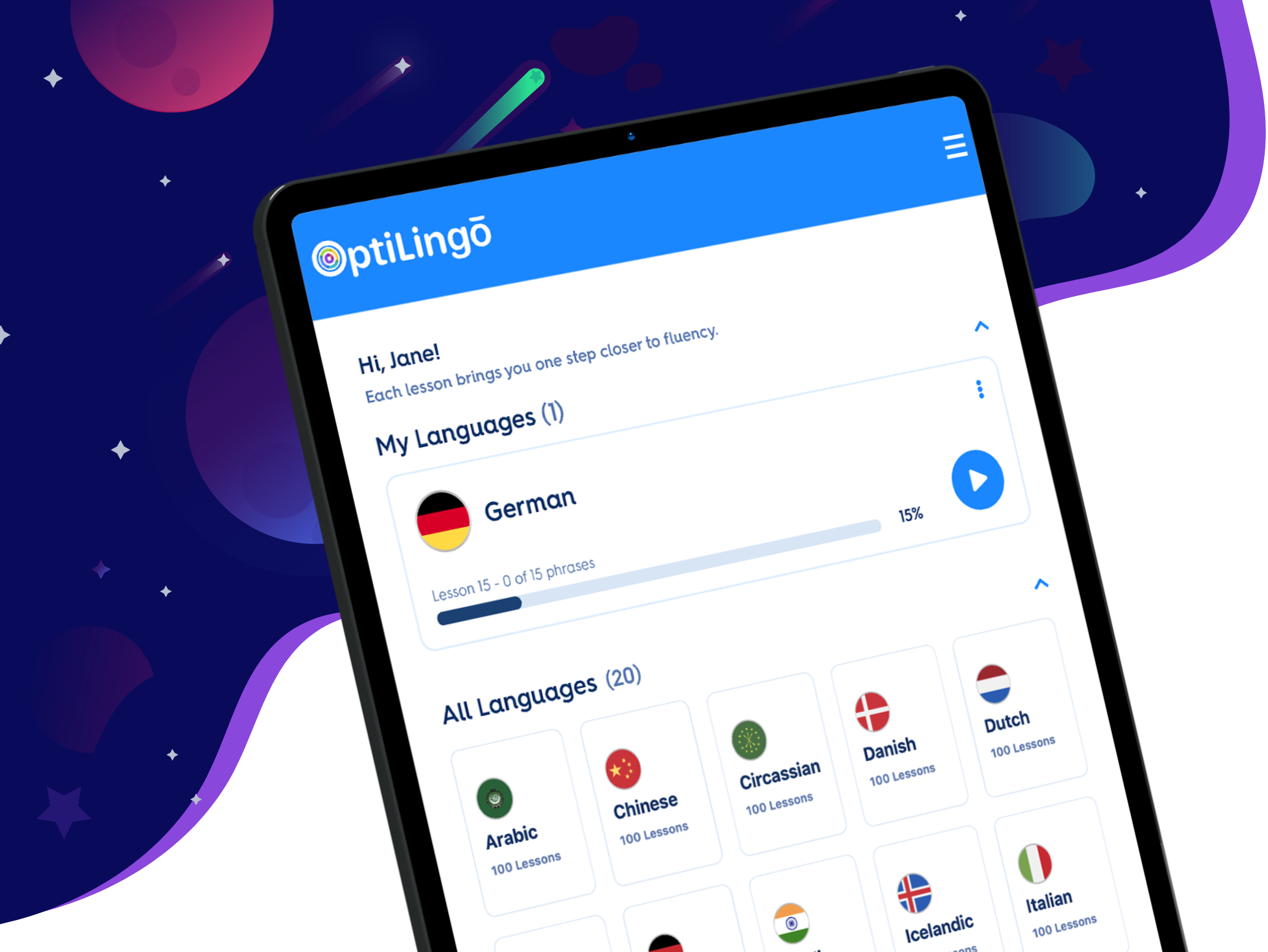

Trying Various Language Learning Platforms

I purchased and consumed every commercial and academic language learning course I could get. If Amazon sold it, I bought it. My overseas friends mailed books and lectures in foreign languages to me. I found a way to get into a crash course language seminar at the United Nations. But it didn’t stop there.

I even I attended another rapid teaching program run at Dartmouth College, taught by John Rassias. (He developed the rapid learning methods used by the Peace Corps to teach new languages quickly.)

Unsurprisingly, every piece of content I consumed made the same promise. “Our approach is the fastest, easiest, most effective, and efficient way to learn a new language.”

Of course, everyone makes this claim. What’s the alternative? To say your approach is poorly developed, unproven, time-consuming, and ineffective?

In all the materials I reviewed, I noticed that there was a huge variance in the quality and effectiveness of the materials. But I wasn’t interested in critiquing this or that approach, method, or teaching material. My interests were in helping my students speak a new language with the least amount of time and effort invested.

While I’m certainly not alone in my efforts to achieve that goal, I daresay I’m a bit unique in my motivation. I didn’t start down this path trying to make money or launch a product. I wasn’t trying to build a social media following or achieve Internet fame.

My mission was to try to save my ethnic language from going extinct. And it still is…

Saving the Circassian language

I needed to help fellow Circassians learn to speak and understand Circassian as quickly as possible. And I didn’t have the luxury of resources afforded by larger, more widely-spoken languages.

Aside from materials I developed, Circassian had almost no language-learning materials for non-native speakers. There were no textbooks or methods for people who don’t already speak a bit of the language. And there aren’t many books written in Circassian. Also, modern media like television programs, radio broadcasts, and films are practically non-existent.

At the same time, Circassian is not a language of trade or governance because Russian plays that role in the ethnic homeland of the Circassians. The only reason anyone might want to learn Circassian would be to talk with extended family members living in different countries that speak different languages.

For my students, however, this was a very powerful motivation. Many of them had circumstances similar to my own, and they wanted to hear the stories of their grandparents. Others had tracked down extended family members across countries as diverse as Syria, Jordan, Russia, Israel, and Turkey.

Communicating in Circassian required learning 4 languages: Arabic, Russian, Hebrew, and Turkish. But people are busy, skeptical, and have short attention spans. So, I needed to find a way to get people speaking and understanding as quickly as possible. Otherwise, I’d lose my chance to convince them to stick with my program long-term.

What Works Best When Learning a New Language

I discovered that no one cared about learning formal grammar. The rules are confusing with frequent exceptions. So, I began to focus exclusively on teaching common, useful phrases embedded with high-frequency vocabulary words:

Over the course of nearly a decade, I wrote and re-wrote thousands of phrases and sentences. These materials are at the core of my courses today. After a decade of work, I’ve developed a series of universal phrases that are very short and simple. This makes it easy to pick up and learn a new language.

At the same time, I wrote these phrases in a way that allows them to be mixed, matched, and combined, conveying a variety of very complex thoughts and ideas. Later, as I got more interested in applied linguistics, I realized that the core of my material covered approximately 1,500 unique phrases, over 1,000 high-frequency vocabulary words, and most grammatical structures.

In other words, the content at the core of my method covers around 80 percent of what a native speaker might read or say on a daily basis. Of course, back in the fall of 2016, when Wa’el reached out to me, I didn’t realize any of this. I was just confused and curious to know how Wa’el used my materials to teach himself Turkish.

Teaching Circassian to Non-English Speakers

As my face-to-face teaching efforts progressed, I began to receive requests to share my materials via the web. As I did, others asked to have my Circassian materials translated into Turkish, Russian, and Arabic. These are the primary languages spoken by 99% of ethnic Circassians.

Native English speakers comprise less than 1 percent of the Circassian population. So, of course, I jumped at the chance to expand my reach and help as many people as possible. My decision to ditch formal grammar instruction and focus on phrases and high-frequency words made it a lot easier to translate these phrases into other languages.

I also learned much about the pros and cons of word-frequency lists. I won’t go into the details. But in summary, I learned that aside from some minor cultural issues, high-frequency words are pretty universal.

English, Russian, Turkish, and Arabic are completely unrelated languages. They come from different roots, share different cultures, and developed in different historical contexts. The word “Soviet” might be common in Russian. However, the word “Allah” might be more common in Arabic (and non-existent in Russian). Despite minor variations, though, words like “help” or “hungry” or “mother” or “father” are pretty universal.

I had a small army of ethnic Circassians help me translate my materials, and as before, I continued to learn and refine my methods and materials. Ironically, my lack of computer prowess led Wa’el to use my materials to learn Turkish. Still, there was a need to create something more accessible.

While I consider myself computer-literate, I’m no programmer. My background is in management consulting, so my go-to tools are Excel and PowerPoint. I used the former to look for patterns across my teaching materials, and the latter to develop my teaching materials.

Eventually, I developed my materials into a five-column layout. Circassian was at the far left, with English, Russian, Turkish, and Arabic in columns to the right. These columns laid out every phrase and word into a simple grid pattern.

How One Strategy Helped People Reach Fluency

Now we can return to Wa’el, my fellow Circassian, an Arabic-speaking Syrian refugee living in Turkey. One day, Wa’el had an idea: why not pull up one of Jonty’s Excel files and focus on the Turkish and Arabic words and phrases? I’d never imagined that anyone would use my materials like that. But somehow, it worked.

My universal phrases and high-frequency words covered around 80% of what Wa’el needed to interact in Turkish society. At the same time, he could say things that were never explicitly covered in the core of my teaching materials. That’s because he’d spent so much time developing content that could be mixed and matched using those phrases.

Other Syrian Circassians replicated his experience quickly. And he asked if I could share my materials with non-Circassian Syrian refugees in Turkey who wanted to learn Turkish. Of course, I quickly agreed.

A Language Learning Program Designed to Save a Language

It was one thing for ethnic Circassians to use materials to learn Circassian. That was their purpose. But when I saw Circassians and non-Circassians (in this case, ethnically Arab Syrian refugees) using my materials to learn Turkish, it blew me away.

Quite honestly, it humbled me. And I was happy that something I had produced could help so many people in their time of need. They learned Turkish easily and quickly. And it was helping them integrate into their new homeland. That’s when I decided I could and would fine-tune and optimize my materials to help people learn other languages as well.