Your All-Inclusive Guide to How People Learn Languages

Language separates us from other creatures. Our ability to illustrate abstract thoughts and feelings using an arrangement of characters and sounds makes humans unique. It’s no wonder philosophers have been debating its importance for thousands of years. Scholars and scientists still argue about how we acquire languages today. If you’re looking to learn a language, it’s crucial to know about the basics of major language acquisition theory.

For so many people, learning a new language is incredibly challenging. Even though we’ve all done it at least once in our lives with our native language. Many think it was easy, but that’s far from the truth. You spent YEARS learning your first language. And it was the result of constant practice, exposure, and native speakers (parents/guardians) guiding you to fluency. So, how do we learn a language?

Understanding Language Acquisition Through Theories

To begin to understand that, you need to look into the main concepts of language acquisition theory. Keep in mind that these are just theories. They have positives and negatives, and some of them even have conflicting views and parts that have been argued against using scientific evidence. Either way, they give insight into how we learn a language.

And as someone on the journey to learn a new language, having an understanding of the language learning process is CRUCIAL. Armed with it, you’ll know what works, what doesn’t, and how to chase after your dream of learning a new language to finally achieve fluency FASTER. These are the 7 leading language learning theories by leading thinkers that have helped shape how we pursue language learning today.

1. Plato and Innate Knowledge

Best known as the famous student of Socrates and one of the greatest philosophers, Plato is where we begin our journey to understanding the nature of language learning (~400 B.C.). One of his more predominant ideas was that human beings are born with innate knowledge (a priori knowledge). In short, people come into the world knowing things they aren’t taught.

Human beings don’t live a long time (they certainly didn’t 2000 years ago) and yet they accomplish so much in that limited time. This is known as, “Plato’s Problem”. Plato believed that some knowledge, including language, was innate. This was why most people can talk early on in life.

Plato set it off from the start. From this point, linguists go back and forth trying to figure out whether or not we’re actually already born with the abilities to speak a language or if we have to learn everything on our own. As you will see, the debate is not clear cut.

2. Descartes and Cartesian Linguistics

You may have heard of famous the French philosopher and mathematician Descartes. And if you haven’t, you may be familiar with this famous saying, “Cogito ergo sum,” otherwise known as, “I think, therefore I am.” As a philosopher, Descartes spent a great deal of time trying to understand what we can say we know with absolute certainty. At the end of the day, he mused, the only thing we know for certain is that we exist. And we can prove that with our ability to think.

Descartes didn’t write Cartesian Linguistics. In fact, he wasn’t really concerned with language-learning other than the fact that it was something people did naturally. His ideas, however, influenced later language theorists, mainly, Noam Chomsky (who we’ll discuss in a moment).

Descartes believed humans to be largely rational creatures that needed language to interact. Our ability to use language creatively sets us apart from the communicative elements of other species. We can rationalize and communicate our position in the world to each other as thinking, speaking beings, no matter where we exist on the planet.

To Descartes, learning a language meant finding similarities between your own and the target language. Then, you merely manipulating already existing structures in your minds through external experiences to learn a language.

While there’s some truth in these views, it doesn’t account for languages that vastly differ from Western ones. And his thoughts detail little on the best way to go about learning a language.

3. Locke and Tabula Rasa

Tabula Rasa, aka, the blank slate, is one of philosopher John Locke’s more popular ideas (1690). In it, he argues against innate knowledge (or knowledge from birth). Instead, he believed that we’re all born as blank slates. And as we go through life, our experiences write knowledge on that slate. He also argued that we learn everything through our senses.

If you’re learning a language right now, you probably feel this way. Every lesson, every step in your journey towards fluency may feel like writing new information into your mind as if it were a blank slate…

However, as you soon see, there are many ideas of thought that differ greatly from this idea. Still, when you consider how we learn some ideas through school and experience, there may be some truth in this Think about how you study subjects like History, Algebra, Philosophy. Some of the concepts may have seemed so alien that when you discovered them, they were like little epiphanies.

While these 3 philosophers mostly talked about language-learning in passing, our next 4 theories focus directly on language-learning.

4. Skinner and the Theory of Behaviorism

B.F. Skinner agreed with Locke built his Theory of Behaviorism onto his concepts and behavioral psychology. His language acquisition theory says that all behavior is in response to surrounding stimuli. And he applied this to language learning through something operant conditioning.

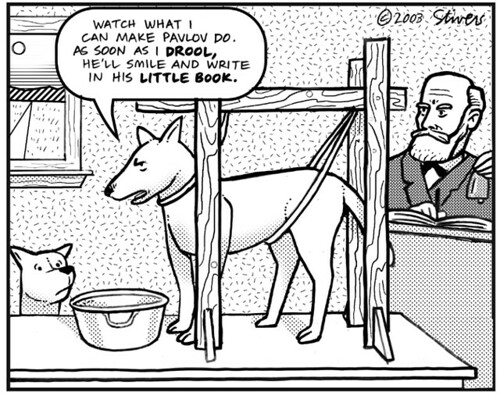

Classical conditioning may be familiar to you. Pavlov’s Dogs is a famous example of this. Pavlov rang a bell and then fed dogs. Soon, the dogs associated the sound of a bell ringing with food and would salivate (whether or not they were actually given food).

Operant conditioning goes one step further…

Skinner applied the methodology behind classical conditioning to the way children learn languages. This resulted in the Behaviorist Theory of Second Language Acquisition. Operant conditioning is the use of positive and negative reinforcement to change behaviors. You can see the effects of this approach with dated and ineffective traditional learning models for second language instruction:

Audiolingualism attempted to establish language learning as a habit through dialogue and drills. Success received positive reinforcement; failure received negative reinforcement. (Demanding a child repeat a request with “please” before delivering on demands, for instance). As a result, the priority focus was on error correction/prevention. Successful language learning is no more than the application of effective operant conditioning, according to Skinner.

There are problems with this language acquisition theory, however. It excludes meaning while creating a stressful learning environment that penalizes learners who make mistakes. This results in many people studying a language in a way that allows them to pass tests, but they cannot hold a conversation.

Also, mistake-making is an essential part of language-learning, Skinner’s theory penalizes it. This can result in learners giving up before they made any progress in learning a new language.

One component of this language acquisition theory that holds weight though is the importance of feedback in some form. Language-learners need feedback for success. They also need a feeling of accomplishment to move forward in their language learning studies.

5. Chomsky and Universal Grammar

Famously, Noam Chomsky argues against many of Skinner’s Theory of Behaviorism with his own Theory of Universal Grammar (the 1950s). This was pretty much the antithesis of Skinner’s theory. Chomsky believed in at least some innate ability in humans for language and a limited number of ways to organize language in our minds. His proof was the fact that there are some universal elements in all languages.

Essentially, we’re all born with the ability to learn languages as a result of a Language Acquisition Device (LAD). This is a theoretical component of the mind that allows anyone to acquire a language. Building off of the nativist theory of language and some of the previous ideas of thought covered here, it shows that people have a capacity to learn a language in everyone from birth.

There is some truth to this. Babies, for instance, have the ability to hear and make any sounds made from any language up until a certain point in development. Also, babies are language-learning machines. They acquire an exceptional amount of knowledge about language in the first years of their lives compared to other topics (like math, reading, abstract thought, etc.). And young children can develop accent-free language abilities up until a certain point as well.

There’s the issue of the poverty of stimulus, or that children simply cannot be exposed to every aspect of language in their environment. Despite this, there are some grammatical mistakes children never make. For instance, you’ll never hear a child mix up word order like this, “Doing are you how?” Instead of, “How are you doing?” These mistakes simply don’t happen.

While his language acquisition theory definitely goes further than Skinner’s theory in explaining how to learn a first language, it really doesn’t apply to secondary language-learning. Instead, it simply reinforces that there are similar elements involved in learning a language. And there are issues with its application to non-western languages as well.

6. Schumann and The Acculturation Model

John Schumann looked specifically at how immigrants learn a new language once they relocate to his Acculturation Model. The Acculturation Model (1978) looks at the sociological and psychological impact of relocation on language learners.

Instead of thinking about language-learning in terms of learning for pleasure, he examined it when it was a necessity. Immigrants, migrant workers, and their children learned a new language with far more pressure from social and psychological areas. And this pressure either resulted in success or failure.

Cultural identification, he argues, is vital to the individual. And if an immigrant’s language was roughly equal socially to the language of their new home, they were more likely to learn the language. The same was true if the cultures were similar. Schumann points out 8 different factors that influence how immigrants evaluate just how closely their culture connects with another.

Schumann’s 8 factors:

- Attitude Factor: If cultural groups have a positive attitude towards each other, there’s a greater chance for language-learning to occur.

- Cohesiveness: The larger the group of similar language speakers, the more they interact with each other, and the less likely language-learning is to occur.

- Cultural Congruence: The more similar two groups are, the greater the chance of repeat contact between them that promotes language-learning.

- Enclosure: If there are more opportunities for learners to interact with native speakers (through schools, jobs, clubs, etc.), there will be a greater chance of language-learning.

- Integration Pattern: Is there a desire to integrate or resist the new language?

- Intended Length of Residence: The longer the stay, the increased likelihood of language-learning.

- Size Factor: If the language-learning group is too large, they will tend to group together, reducing the likelihood of language acquisition.

- Social Dominance: How important is it to learn this language?

He also points out the importance of attitude, culture shock, and motivation for influencing the psychological aspects of language learning. His theories were vastly different than previous language acquisition models because he looked at the individual person and not humanity as a whole.

As a language-learner, you can tie his theory to the importance of motivation behind language-learning. The more motivated you are, the more you want to learn a language, the more likely you are to succeed.

7. Krashen and the Monitor Model (Input Hypothesis)

Stephen Krashen offers the most practical out of all these theories because his position gives you an actual strategy you can use to learn a language. The Monitor Model (1970s – 1980s) is a set of 5 hypotheses that build off of each and outline the process everyone goes through to learn a language.

While parts of the language acquisition theory have been disproven or argued against, overall, modern language-learners and instructors gravitate toward these views.

Krashen’s 5 theories on language acquisition:

- The Acquisition-learning Hypothesis: Speech isn’t the priority. Listening is. Learners begin to understand a language by listening in an immersive environment. Only once a learner has had enough exposure to the language can they begin to speak it.

- The Input Hypothesis: Language-learning comes from having access to comprehensible input, or material that’s challenging but still understandable. If it’s too complex, people don’t learn. If it’s too easy, people get bored.

- The Monitor Hypothesis: As we develop, we build an internal filter designed to prevent us from making mistakes. This filter can interfere with the language learning process because learning happens through mistakes.

- The Natural Order Hypothesis: Language has layers and complexities. People cannot understand complex syntax and grammar structures before people acquire the necessary abilities beforehand. An understanding of grammar happens naturally.

- The Affective Filter Hypothesis: Stress inhibits learning. To maximize language learning results, people should learn in a near-zero/zero stress environment. This will allow learners to be at ease to explore the language.

This theory lays out the differences between language learning and language acquisition. Krashen argues that we all learn language subconsciously and universally. He compares it to seeing, eating, and other uniform human activities. As a result, learning is a far more conscious effort that needs formal correction.

His theories appeal to new language-learners because it removes boring drilling and memorization along with stressful performance requirements of traditional language-learning classes off the menu for students. And in the end, it makes learning a language feel more organic and smoother than what most people remember from their high school and other language classroom experiences.

Understanding Language Acquisition Theory Promotes Fluency

By themselves, none of these theories will help you learn a language. Instead, they serve to illustrate the process behind language learning itself. And they help you map out the thought behind how people process knowledge and achieve fluency. This is vital for you as a language learner.

Why?

Traditional language learning methods have a high failure rate. That’s because they still cling to dated practices. Positive and negative reinforcement simply doesn’t work. Rote memorization and drilling aren’t effective because language isn’t a set of multiplication tables, it’s a tool. Treating language as a subject to be studied and not used leaves people freaking out when someone tries to have a conversation with them.

Knowing this goes a long way to saving you time and money on your journey to learn a new language. You’ll avoid broken and dated programs that only waste your time and money while producing few results. Instead, you’ll choose the best language-learning platform out there, built form theories that work.

OptiLingo is one such program. Using effective strategies like Spaced Repetition Systems and Guided Immersion, Optilingo exposes you to popular phrases with high-frequency words, so you can start SPEAKING not typing your new language, fast.

Want to find out how to rapidly reach fluency? Check us out today!