It’s normal that language learners would want to speed up the process of learning a language. Learning anything from the ground up is difficult. Many learners want to rush through the hard parts: the mispronunciations, the miscommunications, the forgetting of a basic word, etc.

But, it takes time to encode new content from short-term to long-term memory.

It also takes time to transfer passive memory into active memory. Once knowledge is active, you can use it with ease. But getting there is a time-consuming process that involves repetition. You can’t escape repetition.

Your brain needs repetition to encode new memories. The only way to learn faster is to maximize your cycles of repetition, and even that has limits.

Learning a Language through Repetition

In 1967, Dr. Paul Pimsleur published a popular article illustrating that it takes an average of seven repetitions to process information into long-term memory. While Pimsleur fails to point out his methodology or data, he notes that he used intervals ranging from five seconds to two years to come to these results.

Still, he never states why he chose those intervals. This is a good jumping-off point, but without knowing the methodology that Pimsleur used, it’s difficult to replicate his process and test it for ourselves.

Based on my experiences and incorporating the algorithms of prominent Spaced Repetition Systems in use today, I would argue that 10 to 20 repetitions are ideal for language retention. Going below 10 repetitions loses the benefits of encoding information into active recall, which results in you learning in a passive manner.

This makes you more like a robot without a hard drive to store the language information, and you’re just mindlessly repeating sounds. Consequently, your efforts won’t yield the highest results.

The problem with establishing a minimum is that it creates the wrong mindset. Some words and phrases take longer or shorter to encode than others. Finishing 7, 15, or 80 repetitions doesn’t guarantee victory.

Encoding information is a constant process as memories fade over time. If you don’t use it, you lose it. This is especially true with language learning. Regularly exposing our brains to critical information is part of the retention process.

How Many Repetitions Are Enough?

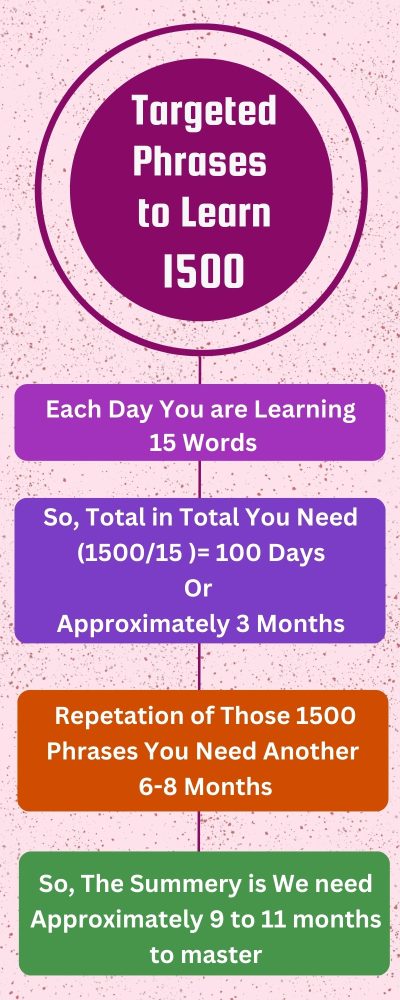

If you were to aim for an average, you could reasonably say that 15 repetitions over six to eight months would result in mastering new information.

For example, let’s assume you want to learn 1,500 phrases in your target language. As a result, you study 15 new phrases each day, every day, without missing a beat. After 100 days, you will reach the last of your 1,500 phrases.

But on that last day, you’d still need another 6 to 8 months for the repetitions of those last phrases. And because 100 days is a little over three months, you’d need between 9 and 11 months to master all of your target information.

Even if you went faster and pushed your brain to its limits, learning 50 phrases a day, you’d still need 7 to 9 months – and you’d sacrifice mastery in the process.

A Polyglot’s Secret Weapon: The Visual-Spatial Loophole

There is one loophole you can use to learn faster. Research shows that people struggle to learn words that are presented abstractly.

Imagine if you had to memorize this list of words:

- Apple

- Beautiful

- Book

- Bright

- Carried

- Down

- Grandmother

- Green

- Her

- Mountain

- Old

- Pie

- Red

- Waiting

- Warm

- Was

- Where

- With

- Woman

How successful do you think you would be? How long would it take you? What do these words even mean when they are presented alone? If you needed to study these words, chances are you’d eventually string them together in an effort to provide some context.

As a result, you might come up with a sentence like this: “The beautiful woman carried a bright red book down the green mountain, where her old grandmother was waiting with a warm apple pie.”

Studying that sentence and visualizing the story would yield far greater results than trying to remember each word individually.

We do this all the time.

When we enter a new situation, our brains quickly map out the area to become familiar with it. This is because we’ve evolved to encode visual-spatial memory as part of a survival mechanism. It’s an innate reaction within us to make a connection between a new situation and a situation we already know so that it’s easier to remember it.

Serial polyglots—people who learn lots of languages—can exploit this loophole to learn languages faster.

Once they have a firm foundation of their target language, they move past basic vocabulary and into consuming books, movies, music, and other mediums that provide context for the brain to retain greater volumes of information faster.

Using these mediums allows learners to digest their target language in oral, written, and auditory forms. These different contexts deliver language information to the learner in the form of metaphorical cinder blocks. They can build a school of knowledge on top of the firm foundation they established with basic vocabulary and grammar.

The more learners expose themselves to movies, music, books, etc., the more building blocks they create to master their target language quickly.